Healthy Pregnancy, Birth Linked to Genetic Diagnosis of Classic-like EDS

Note: This story was updated April 1, 2021, to note that the patient’s medical history included an inflammation of the peritoneum, not the perineum.

Physicians should determine a patient’s specific type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) by identifying the underlying genetic mutations, as this is needed to best manage possible complications.

This conclusion stems from a recent case report of a woman with EDS, who carried a normal pregnancy to term.

The report, “Novel gross deletion mutation c.‐105_4042+498del in the TNXB gene in a Japanese woman with classical‐like Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: A case of uneventful pregnancy and delivery,” was published as a letter to the editor in The Journal of Dermatology.

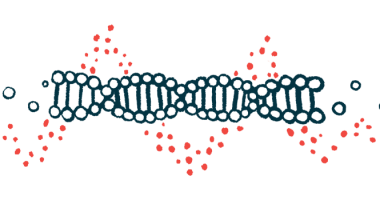

EDS comprises a group of inherited connective tissue disorders that are collectively characterized by abnormally flexible joints, stretchy skin, and fragile tissues. They are due to problems with the production and processing of collagen, a key component of connective tissue.

Differences in clinical characteristics and mutations result in 13 types of EDS being internationally recognized. Although the collagen genes — COL5A1, COL5A2, and, more rarely, COL1A1 — most commonly cause EDS, less frequent mutations can be observed.

Classical-like EDS (clEDS) is one such subtype, stemming from a mutation in the TNXB gene, which carries instructions for the tenascin-X protein. Tenascin-X regulates collagen deposition and forms a part of the extracellular matrix, a collection of molecules outside the cells that helps provide and maintain tissue structure.

Researchers from Japan described the case of a pregnant woman, later diagnosed with clEDS caused in part by a newly seen mutation in her TXNB gene. The woman, 31, had a normal full-term pregnancy and vaginal delivery with no life-threatening complications.

She was referred by her obstetrician to a dermatology office at four months into the pregnancy, due to complaints of abnormally flexible joints and stretchy skin that led to the disease being suspected.

Neither her parents nor her two paternal half-sisters shared these symptoms. Her own medical history consisted of a broken finger and left arm, an inflammation of the peritoneum (which lines the abdomen in the pelvic area), and rectal inflammation or diverticulitis.

Her clinical findings were compatible with an EDS diagnosis. As managing her pregnancy depended upon her EDS type, the dermatology team performed genetic sequencing to identify specific EDS-related mutations.

They discovered two deletions — mutations involving lost DNA — within her TNXB gene. While one was a known mutation, the other had not been reported before. She was diagnosed with clEDS caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the TXNB gene, meaning that each mutation occurred in a different gene copy.

The researchers subsequently found that each of her parents were mutation carriers.

Diverticulitis is one of several symptoms that can occur in cases of clEDS. Others include gastrointestinal bleeding, hemorrhoids, and rectal prolapse (when the rectum, the large intestine’s lowest portion, falls outside the anus).

Although stillbirths and miscarriages have been reported in between 7.7% and 26.3% of cases, and complications related to birth are more frequent in patients relative to unaffected individuals, this woman’s pregnancy was normal and birth occurred with no serious complications.

Her medical team was alert to disease-related risks that include “post-partum haemorrhage, perineal tear, and uterine/vaginal prolapse,” the scientists wrote.

They noted that EDS should be considered in patients who present with abnormally flexible joints, stretchy skin, and family history.

“The dermatologist,” the researchers concluded, “should willingly perform mutation analysis for the determination of EDS type to manage various complications in all kinds of life events.”