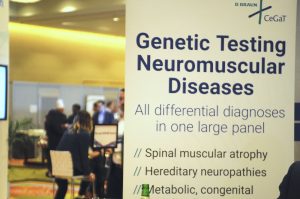

Eurordis Urges Expansion of Newborn Screening Initiatives Across Europe

Written by |

European authorities must step up efforts to screen babies for a multitude of genetic disorders, a panel of experts suggested during a May 14-15 online medical conference.

The session was part of the 10th European Conference on Rare Diseases & Orphan Products (ECRD2020) — which was to have occurred in Stockholm, but instead took place online via Zoom.

“We’re interested in this topic because our community feels poorly served by newborn screening,” said Nick Meade, policy director at Genetic Alliance UK, a national charity representing more than 230 British patient advocacy organizations.

Meade said a newborn screening “patient charter” — launched in July 2019 — has already been endorsed by some 50 rare disease groups in Great Britain.

“We care because a child born with a treatable rare condition with an immediate onset can be identified quickly; appropriate care, support and treatment can begin as soon as necessary to minimize the impact of the condition,” Meade said. “Treatments that stop the progression of a condition can be delivered before any impact can occur.”

Timely treatment can result in the quick delivery of medicine, diet or some other intervention that might mitigate some conditions completely. In addition, timely information may help prospective parents avoid a “diagnostic odyssey” and give them the option of making reproductive choices.

“Screening at birth can provide information to parents of a child with a rare condition much earlier than they would otherwise receive it. And the benefit of a diagnosis with rare disease is broad,” Meade said. “The avoidance of an agonizing and frustrating diagnostic odyssey that might take years — and that might deliver some incorrect diagnoses along the way — is an advantage to screening in itself.”

Screening programs vary widely across EU

ECRD2020 attracted some 1,500 delegates from 57 countries and was the first all-virtual conference ever hosted by Eurordis, a Paris-based coalition of national rare disease associations. Eurordis and its co-organizer, Orphanet, used the occasion to appeal to the European Union in Brussels to urgently approve standardized policies to advance the health and well-being of all Europeans.

According to the International Society for Neonatal Screening, the number of conditions for which babies are screened, as of 2018, varied from only one or two in Belarus, Croatia, Latvia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Ukraine, to 20 or more in Austria, Hungary, Iceland, North Macedonia, Portugal, Spain, Slovakia and Sweden. Sadly, Britain does not score highly when it comes to newborn screening, Meade said.

“Research for some conditions requires newborn screening for case identification,” he said. “There are clinical trials currently recruiting overseas that would be impossible to deliver in the U.K. because we don’t have the screening programs.

“Also, also new medicines receiving regulatory approval at the moment require early or pre-symptomatic administration, which is impossible without screening,” he added.

Having a newborn baby screened for an array of potentially damaging genetic conditions also gives parents the opportunity for reproductive choice and planning, Meade said.

“It allows couples to exercise reproductive choices if they want to, and the timing of the learning of this information can be crucial, because without screening, parents might only find out in their child’s third or fourth year of their risk, which means they might miss the opportunity for reproductive choices,” Meade said.

PKU was first disorder to be screened

On the flip side, he said, there are some limitations to newborn screening. These include parental anxiety due to false positives for the short period between the announcement of further investigations and the all-clear, as well as indeterminate results – those who might need monitoring and further surveillance without conclusive diagnosis.

In addition, there’s a risk of over-diagnosis and over-treatment, particularly of conditions with a spectrum including mild forms, as well as stigmatization — the idea that the label of having a condition might be worse than the early diagnosis to a family or an individual.

Furthermore, children cannot consent to the process, which becomes more of an issue with later-onset conditions such as Huntington’s disease and declaration of carrier status.

“Without minimizing the importance of these limitations, the majority of people living with serious rare conditions don’t weigh these issues highly,” Meade said. “That’s largely because they’ve experienced their lives with very little access to information about diagnosis.”

Neonatal screening started in the 1960s and 1970s after phenylketonuria (PKU) turned out to be a treatable condition. PKU is an enzyme deficiency that can impair brain development; it occurs in 1 in 18,000 newborns and the treatment is a diet low in phenylalanine.

In that test, a baby’s heel was pricked, blood was placed on a “Guthrie card” that was mailed to a lab, which tested the blood for the presence of the disease.

“But when this happened, people felt this was such a big possibility – that all children diagnosed with PKU should be put on a special diet as soon as possible,” said Martina Cornel, professor of community genetics and public health genomics at the Amsterdam University Medical Centre. “Even if it was a rare condition, it was an important health problem.”

The potential of genome sequencing

These days, a modern tandem mass spectrometry newborn screening test — introduced in the 1990s — allows for the detection of up to 50 conditions including PKU. And genome sequencing in the newborn could detect at least 884 conditions, said Meade.

Meade said the potential of genome sequencing in the newborn should be examined in a pilot program — though it remains to be seen whether such a program is cost-effective, which conditions should be screened for, and how those conditions should be selected.

“Families affected by conditions that are not screed for at birth face a diagnostic odyssey — thankfully now significantly shortened — plus the missed opportunities for treatment, information, planning and progress in understanding the condition that could have come from a screening program.”

In 2010, only a handful of countries screened for 20 conditions or more: Austria, Hungary, Iceland, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain, said Cornel, who’s also vice-chair of the Dutch Patient Alliance for Rare and Genetic Diseases (known by its Dutch acronym VSOP).

“In the Netherlands, we started screening for PKU in 1974, and in 2006 we added many more diseases. We now screen for more than 20,” she said, noting that some European countries such as Albania still don’t offer newborn screening at all.

“All newborns need to be offered screening programs,” Cornel said. “The goal is to identify infants with conditions for which effective therapy is available. Early treatment can prevent or ameliorate the disease, so that affected children can live healthier lives.”

Other speakers at the newborn screening panel included Richard Scott, MD, clinical lead for rare diseases at Genomics England, Sara Hunt, CEO of Alex, a leukodystrophy charity, and Simona Bellagambi of UNIAMO, the Italian Federation for Rare Diseases.