List of Rare Diseases Tops 10,000 – and Is Growing – New Analysis Finds

Note: This story was updated July 13, 2022, to correct the name of Rare-X’s CEO Charlene Son Rigby.

Nonprofits, scientists, governmental organizations, and the rare disease drug development industry have long cited 7,000 as the average number of rare diseases in the world.

But a new analysis shows there are as many as 10,867 rare diseases globally. And that number can be expected to grow as more discoveries are made, according to researchers.

Indeed, when the authors of this analysis included all rare disease subtypes and parent disorders, which represent similar conditions, the numbers on that list rose to 11,792.

Rare-X, a foundation that focuses on decentralizing and de-siloing patient-owned, de-identified data, reached that conclusion in its latest “Power of Being Counted” report. The 35-page document outlines the methodology researchers used to come to that final figure and what patients can do with its updated information.

“There was a universal acknowledgment that our number was out of date, and that it was time for us to actually have a definitive source that we could use,” Kirk Lamoreaux, a senior healthcare strategist and one of the report’s authors, said in an interview to Bionews, Inc, which publishes this website.

“It’s not just about the number, but about creating a pathway for rare disease communities to go from obscurity into a well-defined disease that’s eventually attractive to researchers,” added Lamoreaux.

Rare-X marks the spot

Charlene Son Rigby, CEO of Rare-X, with her daughter Juno, who has a rare disease. (Courtesy of Charlene Son Rigby)

Charlene Son Rigby, the CEO of Rare-X, said she can relate to feeling invisible. Her 8-year-old daughter, Juno, has a rare disorder associated with mutations in the STXBP1 gene and she recalls the feeling of being alone when she first heard the diagnosis. Their geneticist told Son Rigby her daughter was the only person he had diagnosed with an STXBP1-related condition.

The STXBP1 gene encodes for the syntaxin-binding protein 1, which helps regulate the release of neurotransmitters, or chemical messengers used by nerve cells to communicate with each other. People with the condition do not produce enough of that protein, which can lead to symptoms such as developmental delays, epilepsy, intellectual disability, movement disorders, low muscle tone, and autism.

When Son Rigby’s daughter was diagnosed in 2016, there were only 200 other people with a known STXBP1-related disorder. Now there are at least 1,500 diagnosed patients. Once the disease is better understood, the diagnosis becomes easier to make — and clinical trials can be more successful because clinicians will know what an improvement looks like for that disorder.

The report is the first step in Rare-X’s mission of using patient data to drive disease understanding and diagnosis. The second step will be to better characterize these diseases, a problem researchers encountered in creating the report. Around 2,200 of the rare diseases on the list were very poorly defined, having no more than two individual signs and symptoms described in the literature. The third step will be improving data collection.

“You can’t even develop an effective drug if you don’t know what a patient population looks like,” Son Rigby told Bionews, Inc. “That’s really one of the fundamental principles that we started Rare-X on, which was to build a data collection program and a data collection portal that enabled that collection of data across disorders, and also enable patients to do it.”

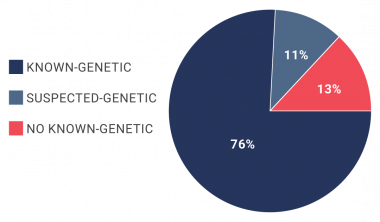

The breakdown of rare diseases by their genetic cause is shown in this graphic. (Courtesy of Rare-X)

Of the 10,867 rare diseases counted, only 5% had a treatment option available. While about 80% of rare diseases counted in the report are theoretically treatable, about 20% are not well defined and thus “not clinically actionable,” the researchers wrote. This is according to data downloaded from two large disease databases on Dec. 11, 2021.

Lamoreaux and his team used Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) and Orphanet as the primary databases to count rare diseases. The OMIM database, which contains descriptions of more than 16,000 human genes and genetic phenotypes, is run by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and is updated daily. Orphanet functions as a kind of rare disease encyclopedia, and includes information on the diagnosis, care, and treatment of more than 6,000 conditions.

Authors of the Rare-X report looked to compare and contrast these databases, making sure to delete any duplicate entries, so they could come to a final number. That was the biggest challenge, Lamoreaux said. Still, they’ve created a repeatable methodology that others can use in the future for developing or adding to a list of rare diseases.

From rare to there

The report also suggests a number of ways patients can ensure their conditions are more widely known, including by seeking community, signing up for genetic sequencing — especially for minority groups who are underrepresented in the Human Genome Project — and staying in contact with researchers working on the condition.

The Human Genome Project met its goal of sequencing the complete set of human genes, but most of its DNA samples came from individuals of European descent.

On the seeking community/networking front, the report suggests tools that can help rare disease communities come together. The Matchmaker Exchange platform helps researchers and doctors find patients with the same genetic variants, while MyGene2 and GenomeConnect offer the same solution for patients and family members.

Son Rigby outlined reasons why rare diseases are undercounted in the first place, and thinks it’s mainly owing to how they are described.

“When you say rare disease, people think, ‘Oh, by nature of the word rare, it’s small, and so it’s unimportant,’” Son Rigby said. “And I think that that overall lens creates many, many downstream issues.”

That problem also manifests in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10), which most of the world’s healthcare systems use to categorize and identify diseases, injuries, and any other conditions.

Many rare diseases are not captured in those codes, and thus they are almost invisible, as Lamoreaux explained. The latest revision, the 11th, features a noticeable increase in codes, but each new update takes time for countries such as the U.S. to adopt.

Now that the methodology framework is put in place, others can do the same analysis in the future, and come up with their own list of rare diseases, the advocates note. That will be necessary given that from 250 to 280 new rare diseases are estimated to be described annually.

“We have the ability to continue to do this over time, because obviously, 10,867 is not going to be the end of the road,” Son Rigby said, adding, “as we understand more about genomics, and even around some of these other areas, we will be able to further delineate additional disorders.”

Ultimately, “The Power of Being Counted” shows how outdated the typical 5,000–8,000 rare disorders estimate is, Son Rigby said. There are larger-scale consequences when people understand the sheer number of rare diseases on any global list.

“That recognition empowers a whole ecosystem of people — researchers, clinicians, patients, even policymakers — around understanding and investing in rare diseases,” she added.