Extensive Rehab Allows Teen With hEDS, Feeding Issues to Forgo GJ Tube

Extensive rehabilitation therapy given by a multidisciplinary team allowed a teenager with digestive problems due to hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS) to forgo surgical feeding tube placement and still gain weight, a case study reports.

“We believe that the combination of patient motivation, multidisciplinary intervention, and medication optimization led to successful feeding in this patient,” its investigators wrote.

The study, “EDS-related Feeding Difficulties: Preventing the Placement of a Surgical Feeding Tube,” was published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition.

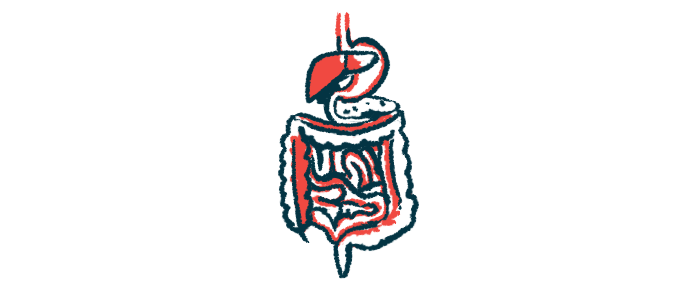

Gastrointestinal (GI) and digestive issues are common for people with hEDS. Symptom management is often difficult and patients can rapidly move to needing dietary supplements and feeding tubes.

Hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) — an abnormal increase in heart rate after sitting up or standing — is also common for hEDS patients. Those with POTS typically require adequate hydration and salt supplements, as well as physical therapy.

Researchers at Children’s Hospital Colorado reported the case of a 14-year old boy with a history of hEDS, POTS, mast cell dysregulation (a condition marked by repeated episodes of allergic symptoms), chronic pain syndrome, chronic headaches, and a concussion one year earlier.

He came to their GI clinic reporting pain while eating, difficulty swallowing, bloating, and weight loss.

An initial imaging test for problems in the upper GI tract revealed a mild delay in emptying of the esophagus. The teen also had evidence of chronic gastritis, or inflammation of the stomach lining.

Three months later, the boy was admitted for dehydration, with an eight-pound weight loss, greater trouble swallowing, nausea, and abdominal pain.

Clinicians suspected the patient had esophageal hypersensitivity — where non-painful esophageal stimuli are thought to be painful. They increased his dose of amitriptyline, given for his chronic pain syndrome, and he was discharged with a nasogastric tube for supplemental nutrition.

During a follow-up appointment at the neurogastroenterology and motility clinic, the patient was diagnosed with rumination — regurgitating food without a physical cause. He was started on a diaphragmatic breathing regimen, a breathing exercise to help strengthen the diaphragm, that eased the rumination symptoms.

His medications included those for chronic pain syndrome, POTS, mast cell dysregulation, nausea, and vomiting. However, his GI symptoms continued to evolve.

During a gastric emptying study, used to diagnose issues with stomach motility (movement of food in digestion), the teen had persistent vomiting and had to be hospitalized.

He was rehydrated and treated with pyloric dilation, given for a sustained delay of gastric emptying. But his abdominal pain and nausea persisted. Treatment with prucalopride was initiated to aid stomach motility.

The patient and his family ultimately requested a gastrojejunostomy tube — inserted into the small intestine for supplemental feeding — because the visibility of the nasogastric tube was leading to bullying at school.

A multidisciplinary team, including a neurogastroenterologist and motility specialist, a chronic pain specialist, a complex care pediatrician, a social work, and a patient representative, met with the family to discussed non-surgical options.

The boy was admitted to the GI service. At the time, he had lost more than 10% of his body weight and his nutrition intake was inadequate.

Admission included feeding tube removal, fluid infusions and oral feedings, daily physical and eating therapy, and intensive psychologic support. The patient was also given one-to-one help in documenting symptoms and focusing on symptom coping.

“Psychologic support included increasing patient emotional awareness and identifying coping mechanisms for the patient to use during distress,” the researchers wrote.

Prior to discharge, he was required to tolerate a recommended amount of daily calories by mouth, along with small amounts of solid foods.

The patient continued from his home to work with pelvic floor physical therapy, weekly feeding therapy and dietician appointments, cognitive behavioral therapy, and make monthly clinic visits. All providers reinforced the goals of oral eating, coping with heart rate fluctuations, core, hip, and pelvic stabilization, as well as breathing techniques.

At the study’s end 14 months post-hospitalization, the teen was continuing to meet his nutritional and hydration needs orally without formula supplementation. His body mass index (a measure of body fat) had improved with a 19-pound weight gain. He continued with daily medications for gastric motility, chronic pain syndrome, and POTS.

“Due to functional GI disorders being the most commonly associated cause of symptoms, we find that encouraging gut motility and altering sensory processing can clinically counteract these effects and recommend avoiding the placement of surgical feeding tubes or central lines for long-term nutrition if possible,” the investigators wrote.

“We propose that medications and intensive multimodal therapies in the inpatient setting should be attempted before surgical intervention in EDS patients with oral feeding difficulty,” they concluded.