Features of vEDS seen in woman with classical EDS: Case study

Case shows genetic testing is key to a correct diagnosis in Ehlers-Danlos

A woman diagnosed with the classical type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) showed features of vEDS, or vascular EDS — a subtype that affects blood vessels and is considered the most severe form of the disease — according to a case study.

Researchers say this unusual case highlights the importance of genetic testing for getting a correct diagnosis from among this group of genetic disorders that affect the body’s connective tissues.

The patient, in her mid-40s, had an aneurysm, or bulge, and tearing in her major arteries — symptoms normally found in vEDS — but genetic testing ultimately led to a classical EDS (cEDS) diagnosis.

“Vascular surgeons who encounter aneurysms and dissection [tears] in young individuals … should be aware that cEDS can have associated [artery disease] similar to VEDS, thus genetic testing is indicated to establish the diagnosis,” researchers wrote.

Their report, “Iliac artery dissection and rupture in a patient with classic Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome due to COL5A1 null variant,” was published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery Cases, Innovations and Techniques.

Woman, 46, found to have a mutation in gene linked to classical EDS

EDS impacts the connective tissues in the body that provide structure to joints, skin, blood vessels, and other tissues and organs. The various types of EDS are caused by mutations that most often affect the production and function of collagens, a major component of connective tissues.

Classical EDS, dubbed cEDS, usually is associated with a defect in the COL5A1 or COL5A2 genes that code for part of the collagen type V protein. vEDS, meanwhile, is mainly caused by mutations in the COL3A1 gene.

Here, researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine and the Oregon Health & Science University, both in the Pacific Northwest, described the case of a woman with clinical symptoms of vEDS but who carried a mutation in the COL5A2 gene.

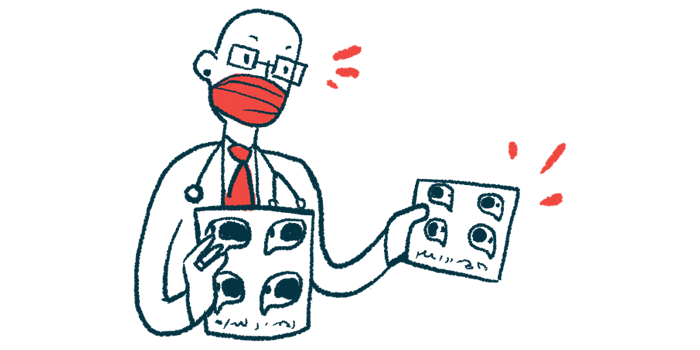

The woman, 46, was initially treated for a dull pain in the right groin. An examination revealed a spontaneous tear of the common iliac artery, known as the CIA, which transports blood toward the pelvic region, legs, and reproductive organs.

A computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan revealed an aneurysm in the right iliac artery. A CTA combines a CT scan with an injection of a special dye to visualize blood vessels.

The patient’s clinical history included a diagnosis of cEDS when she was 34. Her symptoms included easy bruising since childhood, unusually stretchy skin, and hypermobile joints — meaning they moved past the normal range of motion.

Also, at age 40, she had a rupture in the left CIA with severe bleeding, which was repaired by surgery. The woman was admitted to the emergency department the day before that surgery due to pain in the left side of her pelvis.

After surgery, she experienced a hernia at the site of the incision, which again required surgical intervention. Hernias occurs when an internal part of the body makes its way through a weakness in the muscle or surrounding tissue wall.

Further, the woman was found to have high blood pressure, also called hypertension, for which she was being treated when the new symptoms developed.

The researchers noted that members of the woman’s family had undergone surgical repair of the aorta, the body’s largest artery, and that her grandfather had died following the rupture of the heart’s left ventricle, one of its pumping chambers.

The family history and clinical symptoms together were suggestive of a combination of vEDS and cEDS.

Genetic testing confirmed a disease-linked mutation in the COL5A1 gene, and therefore the classical EDS diagnosis.

However, no mutations in the COL3A1 gene were found, which excluded a diagnosis of vEDS. Nor were mutations found in genes linked with abnormalities of the aorta.

Researchers suggest some patients may be wrongly diagnosed with VEDS

Given the patient’s history, she was scheduled for repair surgery of the right iliac artery. Surgery was made urgent after the patient experienced further discomfort and tenderness, leading to imaging scans that revealed a symptomatic aneurysm.

Following certain complications that required a feeding tube on the fifth day after surgery, the patient was discharged on post-operative day 12.

By the time this study was submitted for publication, she had been followed with annual CTA scans for two years. An ultrasound of the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries was planned for subsequent monitoring.

Overall, while “our patient’s presentation and clinical course were suggestive of VEDS and she met the clinical diagnostic criteria for VEDS,” the scientists wrote, “genetic testing was important to demonstrate that she did not have VEDS and that she had a VEDS like condition, in this case cEDS.”

Our patient’s [symptoms] and clinical course were suggestive of VEDS and she met the clinical diagnostic criteria for VEDS. … Genetic testing was important to demonstrate that she did not have VEDS and that she had a VEDS like condition, in this case cEDS.

The team said it’s likely other patients were diagnosed with the wrong EDS type.

“With the increasing utilization of genetic testing, we anticipate that patients who may have in the past been clinically diagnosed with VEDS would be re-classified based on the results of genetic testing,” the researchers wrote.

“Genetic testing [should be] performed to confirm the diagnosis” of cases that may appear to be VEDS, they concluded.