Report: No surgery may be best for aneurysm due to vascular EDS

More conservative strategy may help prevent complications for patients

Written by |

Sometimes, it may be best to not do surgery on an aneurysm — a bulge in a weakened area of a blood vessel — and avoid the risks that come with operating on the fragile tissues of people with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS).

That’s according to experience gained in the case of a man in Italy, diagnosed with vEDS, who was found to have multiple aneurysms. Some were treated with surgery, which caused multiple complications, while others were monitored with imaging and ended up going away on their own.

“The reported complications underline that operative indications should be carefully weighed in these patients,” researchers wrote in a report, titled “Disappearing multiple visceral aneurysms in Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome,” published in the journal Vascular.

“Conservative management … which in this case resulted to be the best strategy, avoided the risks associated with surgical intervention in such fragile tissues,” the team concluded.

Report describes case of man, 34, with vEDS

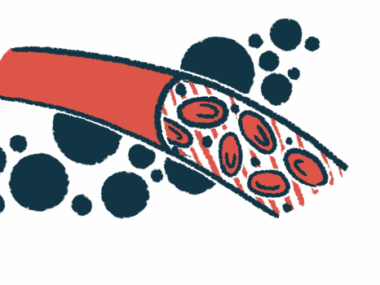

Often considered the most serious of all types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, vEDS weakens the connective tissues that hold blood vessels and internal organs in place. This can cause them to bulge or tear, which can lead to serious bleeding and organ problems.

The way these complications develop often is hard to predict, and it is very difficult to treat and manage them. Because blood vessels are so fragile, undergoing surgery for an aneurysm may not always be an option for someone with the disease.

Here, the researchers describe the case of a 34-year-old man who was treated in the emergency department for abdominal (belly) pain, which had come on suddenly.

The patient had symptoms of hemorrhagic shock, which occurs when serious bleeding impairs the delivery of enough oxygen to the body’s tissues.

His abdomen appeared enlarged and was tender to the touch. He also had several signs common among people with EDS — a small jaw, known as micrognathia, long and slender fingers, called arachnodactyly, and thin, see-through skin.

A CT scan revealed that an aneurysm in a blood vessel called the splenic artery had burst. The scan also showed fluid around the spleen and the liver, and two other aneurysms: one in the right renal artery, which supplies one of the kidneys, and another in the common hepatic artery, which supplies the liver and other organs.

Once the patient’s vital signs were stable, a procedure called coil embolization was performed to treat the splenic artery aneurysm. This involved passing a small coil through a thin tube called a catheter inserted into a groin artery, which was done to block blood flow into the aneurysm.

The procedure resulted in splenic infarction, which occurs when blood flow to the spleen is blocked, leading to tissue death. For this reason, the patient underwent a splenectomy to remove the spleen.

The patient recovered without any complications after the surgery and was allowed to go home after staying in the hospital for seven days.

Surgery for 1 aneurysm deemed successful in follow-up

A follow-up CT scan performed one month later showed that the treatment for the splenic artery aneurysm was successful and that the two other aneurysms were stable.

However, the scan also revealed a new aneurysm in the left subclavian artery, which starts at the aorta, the body’s largest artery. This new aneurysm was likely a result of the coil embolization procedure.

Another procedure called endovascular exclusion was performed. This involved accessing the left subclavian artery through the common femoral artery in the right thigh and placing stents (small tubes) to prevent blood from flowing into the aneurysm.

After four days, the patient was discharged from the hospital, and started on metoprolol to relax blood vessels and slow down the heart. He also was given acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel to prevent blood from clotting.

A genetic test found a mutation called c.683G>7 (p.Gly228Val) in the COL3A1 gene, that is usually mutated in people with vEDS. The researchers stated that this mutation had not been linked to vEDS in previous studies.

A CT scan taken three months later showed that the left subclavian artery aneurysm was blocked off from blood flow. However, the procedure had likely resulted in a new aneurysm in the right common femoral artery. To seal the new aneurysm, a procedure called end-to-end anastomosis was performed.

Two years later, a follow-up CT scan confirmed that the repairs made to the aneurysms were successful, and that the untreated ones continued to shrink on their own.

Surgical or [other minimally invasive] repair of arterial abnormalities should be cautiously attempted and possibly reserved to emergent cases or when a rapid evolution [of symptoms] is noted.

“Imaging is a necessary card to play for the surveillance of these patients but the exact role of a routine imaging follow-up has still to be established,” the researchers wrote. Even so, a plan was put in place for the patient to undergo a yearly follow-up using CT imaging.

Overall, the team noted that a more conservative approach — typically employed by clinicians in vEDS cases — appears to be best for avoiding the risks inherent in aneurysm surgery in vEDS patients.

“Surgical or [other minimally invasive] repair of arterial abnormalities should be cautiously attempted and possibly reserved to emergent cases or when a rapid evolution [of symptoms] is noted,” they concluded.