Walking saps more energy from hypermobile EDS, HSD patients: Study

Less efficient gait strategy may help explain fatigue common in these conditions

Written by |

Walking requires significantly more energy for people with hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS) and hypermobile spectrum disorder (HSD), according to a new study from Canada.

According to the findings, people with hEDS/HSD activate their calf muscles more to stabilize a weaker ankle joint during walking and rely more on their hip and knee muscles due to weaker calf muscles. Together, these changes help explain the higher metabolic cost of walking and the greater fatigue commonly reported by people with these conditions.

The study, “To what extent do the muscles and tendons influence metabolic cost and exercise tolerance in the hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders?” was published in Clinical Biomechanics.

People with hEDS or HSD often report chronic pain, fatigue

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a group of conditions that affect the connective tissue, which provides structure to the skin, joints, and other tissues. Hypermobile EDS is the most common type of EDS, characterized by smooth and fragile skin, as well as hypermobile joints, similar to other types. People with joint hypermobility who do not fulfill the criteria for hEDS are diagnosed with HSD.

People with hEDS or HSD often report chronic pain, fatigue, and feeling unusually tired during everyday activities such as walking. Although the reasons for these difficulties are unclear, researchers suspect that changes in connective tissue may alter the mechanical properties of tendons and, in turn, affect the way muscles function.

However, it remains unclear how these changes influence the metabolic cost of walking and make this activity more physically demanding in people with hEDS/HSD.

To investigate this, researchers in Canada compared tendon and muscle function during walking in 11 people with hEDS or HSD and 11 people without these conditions, all of whom completed a series of laboratory tests during a single visit.

People with hEDS/HSD had more stretchy Achilles tendon

The team began by assessing the stiffness of the Achilles tendon, which connects the calf muscles to the heel and helps push the body forward. Participants lay on their stomachs, with their foot against a fixed footplate, while an ultrasound probe measured the extent of tendon stretching.

People with hEDS/HSD had a significantly softer Achilles tendon, meaning it stretched more under the same force compared with people without these conditions. This test also revealed that they were able to transmit significantly less maximal force through the Achilles tendon than controls.

The researchers then monitored the movement of the Achilles tendon and calf muscles during walking and measured the intensity of work being done by the lower leg muscles.

Each participant walked for six minutes on a motorized treadmill at three different speeds — slower than their usual pace, their preferred pace, and a slightly faster pace — in a random order. The preferred walking speed was determined beforehand during an initial 10-minute assessment, and each trial was followed by a 2-minute rest period.

While the overall movement of the tendon and muscle fibers did not differ meaningfully between groups, people with hEDS/HSD showed greater activation in two calf muscles — the soleus and lateral gastrocnemius. This was detected particularly during the early part of the step (early stance), known as the loading phase, when the foot first hits the ground and the ankle absorbs impact.

In this investigation, people with HSD/hEDS showed a significantly higher energy cost of walking and lower muscle strength.

According to the team, this extra activation likely reflects “a compensatory mechanism to maintain joint stability in the face of joint hypermobility, but one which likely increases metabolic cost and contributes to higher muscle fatigue and pain. ”

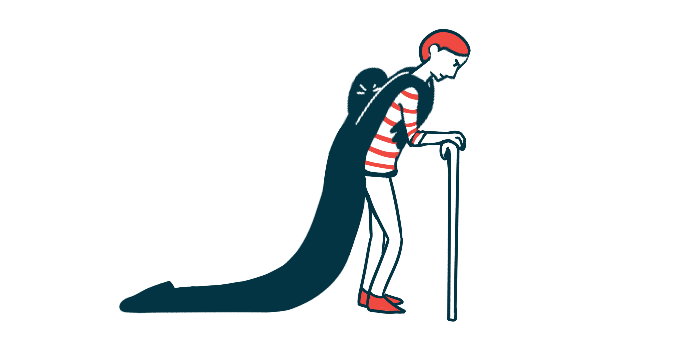

In the later part of the step (late stance), when the heel begins to lift off the ground, people with hEDS/HSD were found to generate significantly less ankle joint power than their healthy peers.

The researchers noted that this weaker push-off, likely influenced by weaker calf muscles, means they may rely more on the hip and knee to move forward — a “less efficient gait strategy” that “increases energetic cost and parallels adaptations observed in aging populations,” the team noted.

In the final two minutes of each walking trial, participants wore a mask that measured oxygen use and carbon dioxide output to assess their energy cost of walking. People with hEDS/HSD exhibited a higher energy cost of walking compared with those without these conditions. This difference was most pronounced at the slow walking speed.

People with hEDS/HSD also reported significantly higher pain levels at every walking speed, and their pain increased at the highest speed. Healthy peers reported minimal pain throughout the tests.

“In this investigation, people with HSD/hEDS showed a significantly higher energy cost of walking and lower muscle strength,” the researchers wrote. “These differences were accompanied by significantly higher ratings of pain and higher muscle coactivation during stance” at all walking speeds.

According to the team, “lower muscle weakness, and higher muscle activation likely [contribute] to higher fatigability in individuals with HSD/hEDS.”