More Research Needed to Assess Benefits of Physical and Mechanical Therapies for Children with hEDS, Study Says

Written by |

There is no scientific evidence supporting a clinical benefit of physical or mechanical therapies to treat lower limb problems in children with hypermobile Ehlers Danlos syndrome (hEDS), according to a pooled analysis of clinical trials.

These findings highlight the need for more quality clinical studies geared specifically toward children that rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of these therapies and guide their use in clinical practice.

The study, “Physical and mechanical therapies for lower limb symptoms in children with Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder and Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: a systematic review,” was published in the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research.

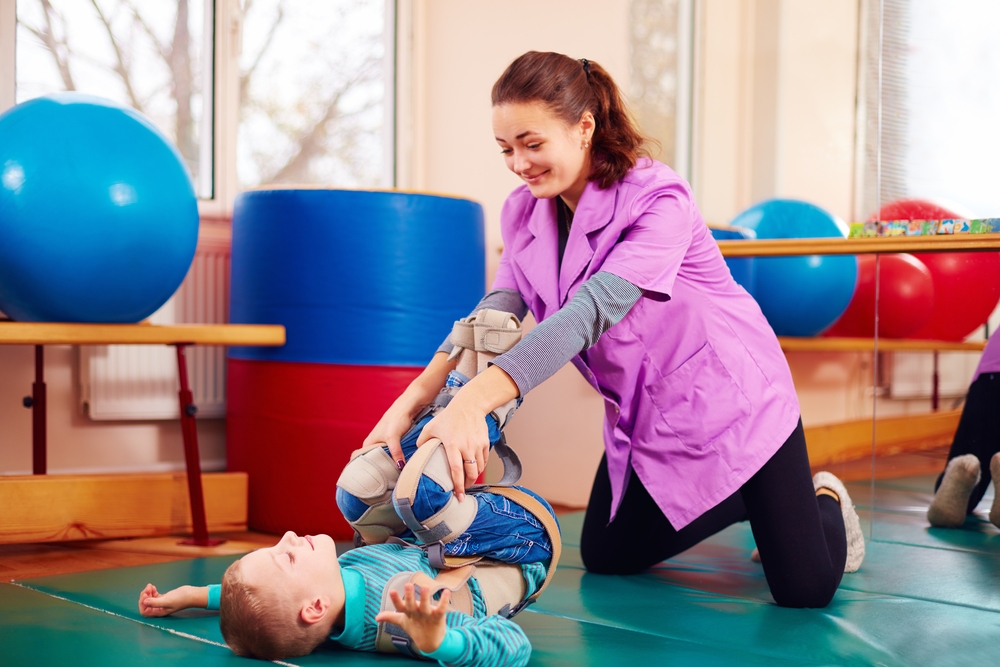

Physical therapies, including strengthening, stretching, and coordination and balance exercises, or mechanical therapies, such as splints or orthoses, are commonly prescribed to treat lower limb pain in children with hypermobility, including those with hEDS.

But there is no comprehensive analysis evaluating the scientific evidence supporting the use of these approaches. Due to this lack of information, “many health professionals are unsure of best clinical practice,” according to the authors of the study.

So far, no studies have compiled the results of randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) that have evaluated the effectiveness of physical or mechanical therapies and focused specifically on children with hypermobility.

RCTs are the gold standard in clinical studies, relying on two important factors: random allocation of patients to each group being tested, and a comparison between an experimental group that receives a new treatment and a control group that receives the current standard treatment, a placebo, or no treatment.

To assess the best available scientific data on the effect of physical and mechanical treatments for children with hEDS or hypermobility spectrum disorder, a team at the University of Newcastle in Australia searched for and analyzed the results of published RCTs evaluating these type of therapies in these patients.

Researchers identified 520 published studies, from which only two were RCTs specifically targeting lower limb problems in hypermobile children. The data from these two trials were then selected for further analysis.

These trials included a total of 86 children with joint hypermobility (48 males and 38 females), ages 7 to 16 years. All participants were diagnosed via the Brighton criteria, a tool that is validated only for adults and not for children.

Both trials tested the benefit of a physical therapy program, and none addressed a mechanical procedure.

One of the trials compared the effect of a six-week generalized physiotherapy program intended to improve muscle strength and fitness versus a targeted physiotherapy program addressing functional stability of symptomatic joints.

The other clinical study evaluated the benefit of an eight-week exercise program to improve muscle strength and motor control over the knee’s neutral range of extension compared with an identical program but within the hypertension range of the knee.

None of the studies proved a clear benefit for the physical therapies tested. No statistically significant differences were found for any of the interventions in terms of child-reported, or a parent’s assessment of, pain, health status, or functional ability of children.

“There is little evidence to guide the use of physical and mechanical interventions for lower limb problems in children with hypermobility,” the researchers wrote.

However the possibility of measuring a clinical benefit or the effectiveness of a new therapy was limited by the small number of participants and the lack of a control group given a placebo program or no intervention.

“Mechanical therapies have not been evaluated in RCTs and results of the two RCTs of physical therapies do not definitively guide physical therapy prescriptions,” the team said.

In their opinion, future research should focus on validating diagnostic tools of hypermobility spectrum disorder and hEDS specific for children, since up until now they have only been validated for adults. They added that future clinical trials should include more participants and maximize follow-up to detect clinically important effects.