Stomach Perforation in Girl Leads to Her Classical EDS Diagnosis

A girl in Saudi Arabia was diagnosed with classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (cEDS) after a seemingly spontaneous perforation in her stomach wall, according to a case report.

With increasing reports of such cases, patients need to be educated about EDS and offered family counseling, the researchers wrote.

The study, “Gastric perforation leading to the diagnosis of classic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: a case report,” was published in the Journal of Medical Case Reports.

EDS comprises a group of hereditary disorders of the connective tissue, which supports, protects, and structures skin, joints, blood vessels, and other tissues and organs in the body.

The condition is due to defects in the production of collagen, a protein that provides structure to cartilage and connective tissue. The clinical presentation of EDS varies with each disease subtype, but gastrointestinal (GI) issues are found in all forms of the disease. Previous research has reported that life-threatening digestive problems are common in the vascular type of EDS, with spontaneous perforations being the most frequent complication.

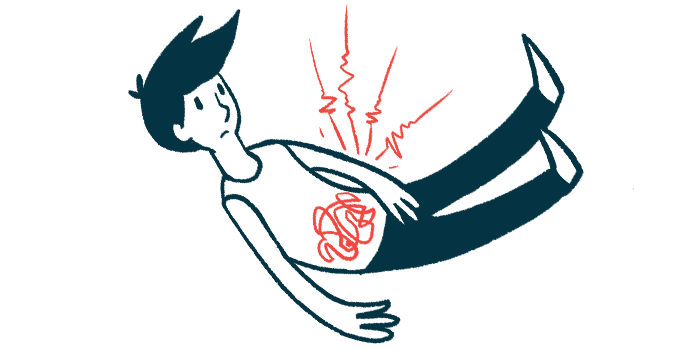

In their study, scientists in Saudi Arabia reported the case of a previously healthy 14-year-old girl who came to the emergency department with abdominal pain and vomiting over the previous three hours. The patient’s family had no history of congenital (at or before birth) diseases.

The girl improved clinically and was discharged with a diagnosis of gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the intestinal lining caused by a virus, bacteria, or parasites.

Three days later, the patient returned to the emergency department with worsening abdominal pain and more vomiting episodes. An examination showed a drop in her blood pressure and a rapid heart rate (up to 130 beats/minute).

Her abdomen was tender when examined. X-rays were taken, and once she was stabilized with the use of intravenous (into-the-vein) fluids, she underwent a CT scan. However, her condition worsened and she showed unstable vital signs, including increased temperature and breathing and lower blood pressure.

The patient was taken to the operating room for an emergency laparotomy, a surgical procedure to examine the abdominal organs.

During the surgery, the doctors found a rupture in the anterior stomach wall with decreased blood flow, or ischemia. This decreased blood flow was also noted over the mucosa layer — the innermost layer — lining the stomach wall opposite the perforation, on the posterior side.

Another surgery was then performed to remove dying tissue (ischemic) from the anterior wall, and the healthy edges were sutured. A drain was placed and the girl’s abdomen was closed. She was then transferred to the intensive care unit with stable blood flow.

After 48 hours, a follow-up laparotomy and endoscopy (to evaluate the blood vessels in the posterior stomach wall) were performed. No further ischemic changes were seen, and the suture was intact. A feeding tube was placed straight into the midsection of the small intestine to provide nutrition.

Post-surgery, the girl remained in the intensive care unit for monitoring and was successfully extubated. She was later transferred to the regular surgical floor, and once she was able to eat, she was consuming six small meals a day due to her reduced stomach size.

She experienced surgical site infection and unsuccessful wound healing, prompting the use of antibiotics and a vacuum-assisted closure device.

A physical exam found the girl had long fingers, mild hyperextensible (extra stretchy) skin, and a positive wrist sign, which means her thumb and fifth finger overlapped with each other. This made the clinicians suspect Marfan syndrome or related disorders, and they requested a DNA analysis. Marfan syndrome is another genetic condition affecting connective tissue.

The analysis revealed a mutation in a collagen gene, COL5A1, supporting a diagnosis of classical EDS.

The patient remained in the hospital for a couple of weeks after surgery. She was discharged after her feeding tube and drain were removed. On follow-up, the girl was doing well.

Overall, “in any young patient presenting with bowel perforation anywhere in the GI tract or any vascular accident without a known etiology [cause], EDS needs to be considered on the differential diagnosis list after excluding other causes,” the team wrote. “Although EDS is a rare etiology, more and more cases of EDS are being reported to be a cause of bowel perforation.”

“The patient must be educated about the involvement of all body organs and the possible complications. In addition, family counseling and genetic tests are obligatory in these cases,” the researchers added.